Those Subterranean Homesick Without a Home Blues

Since I’m finally getting down to telling you more about my trip to Dylan’s birthplace, I figure I might as well greet you in a manner befitting his native Minnesota. Home to America’s only wrestling governor, weigh station for Prohibition-era bootleggers and proud habitat of Babe the Blue Ox, Minnesota is also the friendliest, or at least the most well-mannered, of our forty-eight contiguous united states. You’ve seen Fargo, right? Well, Dylan’s local Hebraic brethren, the Coen brothers, nailed it when they sprinkled their classic with liberal doses of “you betcha”s issuing from thin-lipped mouths. Clearly, the Germano-Nordic immigrants who populated the land of a thousand lakes were determined to bring civility and order to their new surroundings, for these qualities remain there in abundance. Never anywhere in my life have I seen so many strangers making eye contact and saying hello, their pearly whites gleaming as if they were meeting long lost friends. While I’m sure there are folks such as the kidnappers, plotters and money grubbers in the Coen brother’s epic, apparently they keep a low profile when around, not so much revving their Hogs and peeling rubber, as staring off into blue-eyed space, their reveries of murder and mayhem kept politely to themselves.

Perhaps it was because of this that my experiences in Dylan’s birthplace seemed so ironic.

I’d been in Minnesota for nearly a week, first in Minneapolis (where my gal pal Tracey’s brother lives), then in the Braneird Lakes region (the actual site of the “wood chipper” incident depicted in Fargo). Armed with the friendly smiles and greetings of everyone I met, I decided finally to head for the hills, Tracey and I driving up the “iron range” of the North Country to check out the strip-mine-surrounded hometown of the former Robert Zimmerman.

It was a looping, loping drive as twisty-turny as a twisty-turny thing, but after three or so hours and enough Dylan CDs to make my froggy throat ache, we found ourselves pulling into the little town of Hibbing – emphasis on "little." With its main street all but the only street and its intermittently vacant storefronts casting a ghostly stare at our Toyota hybrid, I drove slowly and somewhat reverently to the nearest parking space, ready to head over the local library where I’d heard I could get a “Dylan Walking Tour” map.

On the way there, the almost too bright sun cast a glaring light on the fact that nary a soul was on the streets. It was as if all of Hibbing had been abandoned in anticipation of our visit, the locals tired of the tourists and gawkers and so avoiding the hard rain of inane questions bound to issue from their (or at least my) lips.

True to form, I set off in inane mode almost as soon as we passed through the library’s double doors.

“Any of you know Dylan in high school?” I asked, my eyes lighting on a female staff member who was obviously displeased to be considered a contemporary of the craggy one.

“Here’s your map,” she frowned, avoiding eye contact before turning back to her Dewey Decimal System.

I took it and posed arm-in-arm with the life-sized papier-mâché Dylan by the door, then, as Tracey lagged behind, I headed downstairs to the library’s “Dylan Museum.”

The “museum,” if you could call it that, was largely disappointing. Album covers, magazine clippings and short biographical blurbs one could have found anywhere greeted us first. Worse, as we looked at these, five or so librarians (or perhaps they were Kiwanis Club members?) sat around an oblong table in the center of the space, nattering amongst themselves. You see, the “museum”—a large rectangular room lit by fluorescent bulbs—was also a conference spot, a duel function that seemed to undercut the mystical strain in Dylan’s work just a tad. However, once the meeting ended and we passed from the initial exhibit to the illustrated time-line along the wall, things began to improve slightly. Not only were there pics I’d never seen (grainy black and whites of Dylan’s parents, childhood friends, local hangouts, etc), these were captioned with interesting bits of info that began to hint at what we would see beyond them: “The Androy Hotel, site of Bob Dylan’s Bar Mitzvah party” one read.

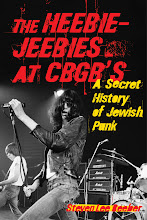

It was an intriguing introduction, made all the more so by my discovery back upstairs that I’d missed a glass booth filled with Dylan memorabilia. Among the copies of Dylan: Lyrics and Behind the Shades: The Biography, there were a surprising number of texts dealing with the gospel-era Dylan. Though that period had lasted only for about five years in the 1980s, the over-representation of it here in the library display case was noteworthy, especially when one further noted that it sat beside books with titles such as Restless Pilgrim: The Spiritual Journey of Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan’s Visions of Sin and Bob Dylan Approximately: A Portrait of the Jewish Poet in Search of God: A Midrash.

Back at the reference desk, speaking to another staff member now (the first refused to raise her head from her books), I asked whether Dylan had ever come to the library or offered to provide items for the exhibits.

“Oh, he hasn’t done anything,” she said, not exactly smiling. “He never comes here and he’s never taken part in Dylan Days [the town’s annual tourist-centric celebration of its native son]. He seems as if he doesn’t want anything to do with us.”

“He never did have anything good to say about us anyway,” the first librarian added, raising her head. “He pretended as if he wasn’t from here, and when he did admit it, he said things that weren’t very nice. We don’t need him.”

“And he doesn’t give anything to help the town, either,” the second librarian interjected.

“Not even with all his money,” concurred the first.

The irony that both were mad at Dylan for badmouthing the town, yet also mad at him for not coming back seemed to escape them.

It soon became apparent that this was the same with almost everyone else from Dylan’s birthplace. For while the town has set up a tour of pivotal landmarks in the young Zimmerman’s life, and a theme restaurant (“Zimmy’s”) has been opened by a true believer at one end of main street, most everyone you speak to about the local bad boy made good expresses resentment at both the kid he was and the man he refuses to be. They say that he was never very friendly in high school and that he wasn’t missed when he left. And they give him the good riddance sneer for his subsequent anti-Hibbing comments. Yet, simultaneously, they attack him for never coming back and, most importantly, for never contributing to the economic well-being of the place he fled as a teen.

From his father’s hardware business to his aunt’s clothing store to his maternal grandmother’s movie theater, one gains a picture of the early Dylan as separate both by choice and consequence, a member of the Zimmerman clan known throughout town for operating many of the town’s businesses, “which is what the Jews mostly did,” as more than one resident told me. “Not that this was bad,” they would add. “That’s just how it was. So you couldn’t avoid interacting with Jews. We weren’t separate, you see, we all got along.”

Well, ok, sort of, I guess. Still, the constant references to the store-owning quality of the town’s Jewish residents and their virtual monopoly on all the businesses in town was a bit disconcerting. As were the all but identical attacks on the former Bobby Z for never having returned to the ol sod, even though they were glad to have seen him go as a youth.

In short, Hibbing has a mixed relationship with its golden boy, one that became glaringly apparent at the tail end of the tour. Fresh from the synagogue where the young Zimmy had read his Haftorah (its congregation now so small its part-time rabbi’s forced to supplement his income as a floor manager at Walmart), we headed to the bar/boardinghouse out back where Dylan’s traveling bar-mitzvah instructor once had stayed during his monthly visits.

The Stardust Lounge was tacky-wonderful in that shadowy, primary-colored way one finds only in Houlihan’s-free small town America. It had an old oak counter lined with red-cushion-topped high chairs and directly across from these all kinds of bottles in front of mirrors filled with clippings from the local weekly’s comics page. The bartender, a too-thin woman with a post-birth midriff below her tank top and above it more teeth missing than in place, was super friendly and upbeat, but disturbing due to her apparent crystal meth abuse. She lined us up a couple of drafts as the somewhat bleary-eyed Ryder-cap-wearing guy to my right told her to stop.

“Where you two from?”

We told him.

“Here to see the Dylan sites?”

Of course.

“Rosy, get them a couple of Bull-Meisters.”

"You don't have to do that," we protested, not exactly sure what Bull-Meisters were.

“Don’t argue,” he said. “You have them. On me. I’ll consider it an insult if you don’t.”

Refusing to risk insulting a fellow patron already bleary-eyed at four in the afternoon (and this a “school day”), we set about taking our drinks in hand and chugging them down as instructed.

“Don’t taste – just shoot them.”

The shots, in all their overly sweet glory, were had, and two more immediately ordered by our new friend, who introduced himself as Jeff, “the guy who can tell you anything about this town.”

First, we wanted to know what Bull-Meisters were.

“Red Bull and Jagermeister. Where you from?”

Boston via Atlanta and Minnesota we explained.

“And you don’t have Bull-Meisters there? Well, you’re missing out ... You know, you look Irish,” he said to me, nonsequitarally.

For those of you in cyberspace who haven’t checked out my book jacket photo, I can tell you that I look anything but Irish. German maybe. Possibly Polish. But Irish? I’ve never heard that one.

“Actually, I’m Jewish,” I said.

His eyebrows went up and down and his bleary eyes focused.

“Jewish?”

“Yeah.”

“But I was talking about your nationality. Why do Jews always say they’re Jewish instead of where they’re from?”

Uh oh. The generic “Jews” who always say the same thing made my stomach tighten. Or maybe it was just the Bull-Meister.

“I guess it’s because the part of Poland where my grandparents came from was almost entirely Jewish since the Poles and Russians surrounding it were extremely anti-Semitic and separated the Jews from themselves since they didn’t consider them part of their country.”

The eyes focused again, revealing more than average intelligence and I realized the moment had passed.

“Ok,” he said. “But this is America.”

It was said more as a peace offering than a renewal of hostilities.

“Right!” I said.

We shared another Bull-Meister, this one on me, and as Tracey began talking to an even blearier half-Indian, half-who-knows-what (he looked like an Asian Jerry Lewis to me), Jeff, the bartender and I set about trading drinking war stories, all of us laughing as the jukebox finally came to my Dylan selection.

Now, let me backtrack just for a moment and point out that this bar, which appropriately enough provided a place of special reverence to its jukebox, did not, however, exactly fill said jukebox with Dylan music. In fact, among the countless albums by ACDC, Def Leopard, Bob Seeger and Led Zeppelin, there was only one disc by their native son, the greatest hits album, one found in jukeboxes everywhere.

How does it feeelllllll...

“So, do your customers not like Dylan?”

Neither the bartender nor Jeff had much to say on the subject.

“I heard he’s not exactly beloved by the town,” I continued.

And at that, I’d opened the floodgates. The same accusations and diatribes, though this time amplified by liquor, issued forth, both Jeff and Rosy the bartender getting in on the action before laughing it off.

“I mean, who cares,” said Rosy with a shrug. “So he doesn’t come back. That’s his choice.”

I worried that perhaps this wasn’t the time to mention what had been on my mind since we’d entered and why I’d originally come to this place (even if I was now finding that the Bull-Meisters had perhaps been more desired than I’d realized). But I went ahead, regardless. Best to do it now if ever.

“Do you have rooms upstairs?”

Rosy and Jeff looked at me skeptically before she said yes.

“Are they part of a boardinghouse?”

"They used to be," Rosy said. "Now they’re apartments."

“Oh, because I heard that Dylan, when he was a kid, used to come here to study for his Bar Mitzvah with a traveling Rabbi that boarded upstairs.”

They looked genuinely interested.

“In fact,” I added. “I read somewhere that it was during those visits, as he paused between his own practice chanting, that he heard his first rock ’n’ roll coming up through the floorboards from the bar.”

“Cool,” Rosy said.

“Yeah,” Jeff concurred.

“Yeah, this was where he first heard and fell in love with rock ’n’ roll,” I said unnecessarily. But I was excited by their excitement. Finally, a joint appreciation of Dylan.

“You should get that mentioned on the Dylan Walking Tour,” Jeff said to Rosy.

“You bet,” she said. “I’m way ahead of you.”

Ah, so that was it. Dylan wasn’t hated for who he was exactly. He was resented for what he wasn’t – or rather wasn’t for the town. A cash cow, a draw, a truly profitable attraction. The boy had gone off and become famous and bought houses around the country. But did that benefit the town at all? Not really. Or at least not enough. Dylan may have made a name for himself, but he hadn’t done so for the town that first called him by his name. He had gone off while they remained here and they wanted something for their pains, their contribution, whatever it was, to his development. They wanted a bit of that crazy, super known feeling. They wanted the riches of renown if not actual dollars. They wanted to know how it feels, you see.

How does it feelllllll, Dylan repeated.

Yes, how does it feel, indeed.

“Another Bull-Meister,” Jeff called.

“This one’s on me,” I replied.